Voters in Turkey weigh the final decision on the next President | World news

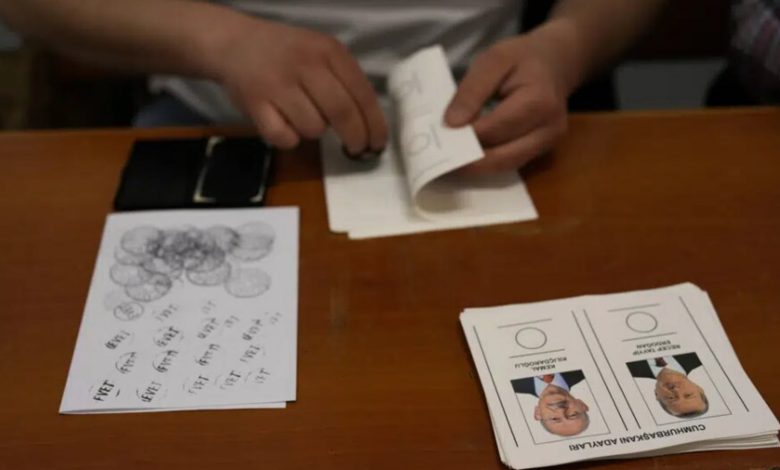

Voters in Turkey return to the polls on Sunday to decide whether the country’s long-time leader extends his third-decade rule or is unseated by a challenger who has promised to bring return a more democratic society.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has been at the helm of Turkey for 20 years, is favored to win a new five-year term in the second-round after falling short of an outright victory in the first round on June 14.

The divisive populist who turned his country into a geopolitical player finished four points ahead of Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the six-party candidate and leader of Turkey’s center-left opposition party. Erdogan’s performance comes without additional mitigation and the effects of the devastating earthquake three months ago.

Kilicdaroglu (pronounced KEH-lich-DAHR-OH-loo), the 74-year-old, has described the race as a vote on the country’s future.

More than 64 million people are eligible to vote when polls open at 8 a.m

Turkey has no exit polls, but preliminary results are expected within hours of polls closing at 5 p.m.

The final decision could have far-reaching effects beyond Ankara because Turkey stands at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, and plays an important role in NATO.

Turkey’s veto of Sweden’s bid to join the alliance and buy Russian missile-defense systems, which caused the United States to withdraw Turkey from a US-led fighter-aircraft project. But Erdogan’s government also helped broker a major deal that allowed Ukrainian grain shipments and avoided a global food crisis.

The June 14 election saw 87% voter turnout, and strong participation is expected again on Sunday, showing voters’ enthusiasm for elections in a country where freedom of expression and assembly is suppressed.

If he wins, Erdogan, 69, could remain in power until 2028. After three terms as prime minister and two as president, the devout Muslim who heads the conservative Justice and Development Party, or AKP, has been Turkey’s longest-serving leader. .

The first half of Erdogan’s term included reforms that allowed the country to begin negotiations to join the European Union and economic development that lifted many out of poverty. But he later moved to curtail freedoms and the media and place more power in his hands, especially after a failed coup attempt that Turkey says was led by US-based Islamic cleric Fethullah Gulen. The priests denied involvement.

Erdogan transformed the presidency from a largely ceremonial role to a powerful office through a narrow 2017 election that abolished Turkey’s parliamentary system of government. He was the first president to be directly elected in 2014 and won the 2018 presidential election.

The May 14 election was the first that Erdogan did not win outright.

Critics blame Erdogan’s unconventional economic policies for the skyrocketing inflation that has fueled the cost-of-living crisis. Many also faulted his government for its slow response to the earthquake that killed more than 50,000 people in Turkey.

However, Erdogan has retained the support of conservative voters who are loyal to him for raising the profile of Islam in a country based on secular principles and for promoting the country’s role in world politics.

In order to woo voters hit hard by inflation, he has increased income and pensions and subsidized electricity and gas prices, while showcasing Turkey’s homegrown defense industry and infrastructure projects. He also focused his election campaign on a promise to rebuild earthquake-hit areas, including building 319,000 homes within the year. Many see it as a source of stability.

Kilicdaroglu is a humble former politician who has led the pro-secular Republican People’s Party, or CHP, since 2010. He campaigned on a promise to reverse Erdogan’s democratic regime, restore the economy by changing to more traditional policies and to increase connections. with the Sun.

In a do-or-die bid to finally reach the country’s voters, Kilicdaroglu vowed to send back refugees and scuttle any peace talks with Kurdish fighters if elected.

Many in Turkey consider Syrian refugees who are under Turkey’s temporary protection after fleeing war in neighboring Syria as a burden on the country, and their return is a key issue in the election.

At the beginning of the week, Erdogan accepted the endorsement of the third place candidate, nationalist politician Sinan Ogan, who won 5.2% of the votes and was not in the race. Meanwhile, an anti-immigrant group that has supported Ogan’s candidate, announced that it will support Kilicdaroglu.

A victory for Kilicdaroglu would add to a long list of electoral losses to Erdogan and force him to step down as party chairman.

Erdogan’s AKP and its allies retained most of the seats in the parliament after the parliamentary elections were held again on June 14. The parliamentary elections will not be held again on Sunday.

Erdogan’s party also dominates the region hit by the earthquake, winning 10 of the 11 districts in the region that have traditionally supported the president. Erdogan is ahead in the presidential race in eight of those regions.

As in previous elections, Erdogan used state resources and his control of the media to reach voters.

Following the May 14 vote, international observers also pointed to the criminalization of false information and online censorship as evidence that Erdogan has an “unjustified advantage.” Observers also said the elections showed the resilience of Turkey’s democracy.

Erdogan and the pro-government media portrayed Kilicdaroglu, who has received the support of the country’s pro-Kurdish party, as collaborating with “terrorists” and of supporting what they described as “ignorance” of LGBTQ rights.

Kilicdaroglu “takes his orders from Qandil,” Erdogan said repeatedly in recent campaign rallies, a reference to the mountains in Iraq where the leadership of the outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, is based.

“We take our authority from God and the people,” he said.

The election is taking place as the country marks the 100th anniversary of its establishment as an independent republic, after the fall of the Ottoman Empire.